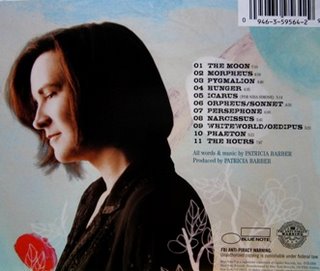

Patricia Barber offers a song-by-song description of the album:

• “The Moon” actually predates my getting the Guggenheim Fellowship [the song opens Barber’s 2002 release Verse]. “I am fascinated with the moon, how writers have written about the moon, and how poets have been moonstruck. I started reading everything I could get my hands on about the moon. I asked colleagues of my partner, who is a professor at the University of Chicago, to send me moon poetry. I thought perhaps I had a new angle on the subject, but wanted to make sure. The Moon, as character here, is a performer, broken-hearted, but she still has to dress up and step onto the universal stage every night. If she doesn’t, it stays dark down here and all Chaos will ensue. This is her dilemma.”

• “Morpheus” is very dear to me because I have sleep issues, bad insomnia. It’s a prayer to the God of Sleep to send his son, Morpheus, the God of Dreams. It is one of my favorite songs of the entire song cycle.

• “Pygmalion” is very much in a classic American song form, written in that 32-bar style. There are a few harmonic variations and of course, what a wonderful story, how he waits for this cold piece of rock, this statue of a woman to come to life. That was easy for me to generalize to the universal question: “Can I will you to love me? Can I will the fantasy to life?”

• “Hunger” is one of Ovid’s fun characters. When I was reading about Hunger I was just dying imagining all the possibilities. She’s such an ugly character, thin and voracious and mean with greenish skin. In our society it’s chic to be thin so I had the idea to simply turn the story on its head and I made Hunger chic and glamorous and mean. It’s dark but it’s funny. It has one of my favorite lines of the entire song cycle: “Now the Hunter is prey and the Hungry are meat...”

• “Icarus”, in my version, doesn’t crash. He just keeps flying up until you can’t see him anymore. I grafted the Nina Simone story onto the Icarus story and dedicated the song to her. It starts with Daedalus, Icarus’s father, crafting the wings. The second verse is about Nina at the Midtown club outside of Philadelphia in her chiffon dress. They both know that only by taking a big risk will you ever fly.

• “Orpheus”, as I wrote it, is an actual sonnet. It is based on one of the most beautiful stories every written. He was a musician appealing to Hades to let his love, Eurydice live again. I tried to find a contemporary angle – so my modern day Orpheus is a gardener. This is a sad, sad song.

• “Persephone” is fun, fun, fun – she’s such a wonderful character. There wasn’t quite enough in Ovid about her. She’s in Book Five – abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld and then in Book Ten as one of the judges of Orpheus’s plea. So I went back to Homer, the origin of the written story of Persephone, and I read Dante because I was curious about Hell. I seized poetic license and created a story in which Persephone ends up liking her power down there. She is the only god who can traverse the upper- and underworlds. She becomes Virgil leading an angel through hell, trying to corrupt her as she is showing signs of weakness. She will use anything at her disposal to get what she wants. It’s a song of seduction.

• “Narcissus” – I had notes written down that this would be one of my “smart” songs because of the obvious double-entendre possibilities. Then I started reading secondary literature about Narcissus and it was very interesting – it was slightly moralistic in its judgment of the danger of “Narcissistic” love as being homosexual. Being gay myself, I thought, why not embrace that idea? If homosexual love is Narcissistic, and you don’t know whether you’re making love to yourself or to the other, how much fun is that? That’s what it’s about and it turned out to be a very sweet, simple, lyrical, beautiful song, with a musical twist in that it’s in a time-signature of 10/4. It could be the gay wedding song.

• “Whiteworld” was the first song I wrote after I won the Guggenheim [the song appears on Barber’s 2004 release Live: A Fortnight In France]. It’s the only song that isn’t titled with a character – it’s about Oedipus. He was clearly a young, arrogant man who killed his father. I read the Sophocles version of the story: “I came to a juncture of two roads” – the bridge of the song is actually Sophocles verbatim. There, an old man hit him. He not only hit him back but he “had to kill them all.” Given historical and current events, the song wrote itself.

• “Phaethon” also wrote itself and is about another arrogant young man – he thinks he can drive his father’s chariot – the chariot of the Sun. But he can’t – he doesn’t have the skill or the maturity so he ends up scorching the earth until there are very few species left. At the end of the story Mother Earth pleads with Zeus to kill Phaethon before every single last species is dead, which he does. It has a lot of obvious modern-day parallels. I asked some wonderful kids from the Chicago Children’s Choir to rap a list of endangered species over the final section of the song.

• “The Hours” are two Goddesses in Ovid. They are everywhere, watching. They simply watch us as we squirm and scream out in pain and they do nothing but mark time. They never lift a finger. So the song is railing against their callousness, and it is an homage to human courage in the face of Death. I read the writing of Primo Levi, an Auschwitz survivor, to try to understand what it feels like knowing death is coming soon. I also consulted my doctor, who took me through the University of Chicago hospitals and talked to me about life and death. It gave me some purchase on the subject. I had to have my favorite choir, Choral Thunder, sing it. If this song doesn’t bring tears to your eyes, nothing will.

“The Hours” is very dear to me – it’s about time, life and death. But it’s also about life as a performance, or more accurately, a performer, writing about our life as a performance. Mythologies starts with a recording of a small tape recorded solo piano performance, the introduction to “The Moon.” It is a distancing technique; it is there to remind you that this story is being told by a performer and that we’re all performers on the universal stage. “The Hours” acts as a matching bookend to “The Moon,” and says, “this performance [is], in fact, last, and sweetly in vain, so let me entertain you one more time.”

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Barber's `Mythologies' breaks ground

August 13, 2006

By Howard Reich

Twenty years ago she was a fledgling lounge singer, dispatching vintage tunes amid the din of conversation at the long-shuttered Gold Star Sardine Bar, on North Lake Shore Drive.

Today, she stands among the most respected singer-pianists in jazz, a blossoming composer set to release the boldest and most substantial work of her career.

When Patricia Barber's "Mythologies" (Blue Note Records) appears in stores on Tuesday, listeners will hear a piece of music with no apparent model in jazz of the 20th Century (or the 21st). For though classically tinged jazz suites date back to at least Duke Ellington's "Black, Brown and Beige" (1943) and extend to epic works such as Charles Mingus' posthumously premiered "Epitaph" (1989) and Wynton Marsalis' Pulitzer Prize-winning "Blood on the Fields" (1997), "Mythologies" stands apart from such behemoths.

Diversity and coherency

For starters, it's an intimate, Schubertian song-cycle based on Greek mythology, as re-examined by an ancient Roman poet (of all things). Moreover, it pushes at the outskirts of widely accepted definitions of jazz, in that it encompasses a pop sensibility at one moment, classical expression the next and passages of hip-hop verse and triumphal choral writing, to boot.

Yet these far-flung expressions cohere surprisingly well in this suite -- just as they did when Barber performed the world premiere of excerpts of the work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in January. The alluring liquidity of Barber's vocals and the chic understatement of her pianism give the music its continuity, while the high craft of her lyrics bring it focus and purpose.

But the artistic heights to which Barber aspires in "Mythologies" may make this release more endearing to serious listeners than to the vast commercial audience, which has made icons of far lesser talents, such as Norah Jones, Diana Krall and Jane Monheit. While these artists have triumphed commercially by reviving role models of the distant past -- particularly the seductive, purring chanteuse of the 1940s and '50s -- Barber has ventured into fresher territory. To her, the female singer-pianist is not necessarily an object of nostalgia and romance but a contemporary thinker with intellectual firepower to burn.

Inspired by another innovative Chicagoan, the theater director Mary Zimmerman, Barber chose as inspiration Ovid's "Metamorphoses," which was the fulcrum of Zimmerman's celebrated stage play of the same name for Lookingglass Theatre, in 1998. Because a jazz composer-pianist does not have actors, dialogue and scenic design at her disposal, Barber has come to grips with Ovid's vast retelling of Greek mythology by crafting her songs as character sketches of particular gods or goddesses.

This conceit has enabled her to bring a jazz sensibility to a remote field of literature, yet she also has managed to transcend the source material.

In "Icarus," for instance, Barber predictably captures the heroic sweep of the young man's famous flight with surging rhythms and soaring melody lines. Yet she traverses beyond the celebrated narrative, as well, singing a verse that alludes to Nina Simone's earliest days as a struggling jazz singer. In so doing, Barber reminds us that great artists, too, take perilous risks in order to fly. Like all of Barber's writing in this suite, the Simone references prove subtle and hauntingly poetic.

In "Narcissus," Barber avoids the obvious theme of self-adoration and dares to explore, instead, the mirror-image qualities of homosexual love. And in "Pygmalion," she turns the heady yearning of an artist smitten with a cold-stone creation into an exploration of unrequited love.

Insomnia to gluttony

Musically, "Mythologies" covers a vast expressive range, from the brooding, late-night blues of "Morpheus" (in which an insomniac protagonist yearns for sleep) to the wicked, snarling satire of "Hunger" (an ode to gluttony); from the dirgelike gloom of "Orpheus" (who grieves the loss of Eurydice) to the glorious, redemptive choral passages of the finale, "The Hours."

Made possible by a Guggenheim Fellowship, which afforded Barber the time to research and create the magnum opus, "Mythologies" bears few similarities to her earlier work -- except that it represents the further development of her gifts as songwriter, which came to the fore in the aptly named CD "Verse" (of 2002).

Given the nature of any jazz musician's career, which requires a great deal of performance in order to stay solvent, it may be a long time before Barber again can find the time and means to devote to a work of comparable import.

Which makes "Mythologies" all the more valuable.